Courage Under Fire: Dispatches from the Battlefield

As wars happen across the globe, it's the reporter's job to cover the drama—even at the risk of his or her own life; as the nature of warfare changes, the reporter has to change with it. Sometimes, when the action gets so intense that putting a reporter in the crossfire isn't worth the risk, others have to carry the burden of telling the story—no matter how awful it is.

Lèonidas aux Thermoplyes by Jacques-Louis David, 1814

“They withdrew again into the narrow neck of the pass, behind the wall, and took up a position in a single compact body—all except the Thebans—on the little hill at the entrance to the pass, where the stone lion in memory of Leonidas stands today. Here they resisted to the last, with their swords, if they had them, and if not, with their hands and teeth, until the Persians, coming on from the front over the ruins of the wall and closing in from behind, finally overwhelmed them with missile weapons.” - The Histories, 7:225

So ends one of the most celebrated battles in history; a struggle that saw a (relatively) small force of 7,000 Greeks led by the Spartan king Leonidas and his personal vanguard of 300—armored from head to foot in bronze, carrying their three-foot-wide wooden-and-bronze hoplon shield in one hand and an eight-foot-long spear in the other—make their last stand on a hot August day in 480 BC in a narrow northern Greek pass called Thermopylae against an overwhelming force of 200,000 Persians (some accounts differ on the actual number) led by their king, Xerxes. Considering the fact that the indomitable fighting spirit of the Greeks—and the Spartans in particular—managed to survive countless retellings through the millennia, one could argue that Frank Miller didn't have to create his graphic novel, and Zack Snyder didn't have to make a movie based on said graphic novel, but one could also argue that it was the thought that counted.

When it comes down to it, the story is also just that. It was finally written down forty years after the fact and retold to Herodotus (he was, after all, a historian), so there's no way it could have been passed off as anything but a secondary source; also, all 300 Spartans died with Leonidas, which meant that if anyone was going to tell their story, it probably would have been the Persians (and they certainly weren't going to talk).

There have been accounts of what happened during a battle practically as long as there have been battles, from the nameless messenger who ran all 26 miles from the beach at Marathon to Athens, proclaimed the Athenians' victory over the Persians, and then dropped dead; to the aforementioned Herodotus' recounting of the Spartans' last stand at the Hot Gates; to even Julius Caesar's conquest of the Gallic tribes from 58-50 BC. The problem with all of them, though, is that they were recorded after the battle took place. Even during the Civil War, messages could only go as fast as a horse could run; while the telegraph cut down reporting time considerably, there was still a noticeable delay between the story and its actual publishing. It would not be until the First World War that communication on the battlefield could be classified as "instant" (as long as the telephone's cable wasn't severed).

First World War

With the invention of the telephone by Scotsman Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, communication between armies was expedited and the use of runners decreased (though runners were still used in case armies lost touch with each other). The telephone also made it easier for journalists to get their stories to their news editors faster, but because of the expectation that war was still a "noble cause" at the time and thus shouldn't be reported negatively, journalists were heavily restricted in what they could talk about. In fact, the government was so concerned with the public's view of war and reporters telling the whole truth—including the negative parts—that they ordered the creation of the Committee on Public Information, with George Creel as its chairman.

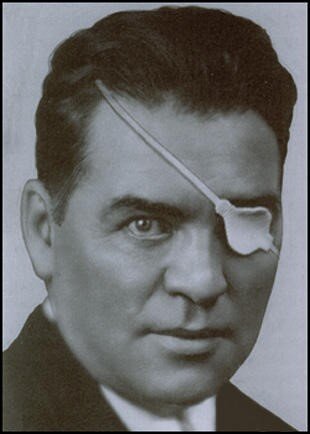

That didn't stop journalists like Floyd Gibbons, who reported on June 6,1918, "I am up at the front and entering Belleau Wood with the U.S. Marines." Unfortunately, Gibbons didn't come out of the battle unscathed—he was wounded in his left arm, shoulder blade, and later lost his left eye.

Second World War

Andy Rooney as a journalist for Stars and Stripes during World War II; he would later be a weekly fixture on CBS' 60 Minutes for over 30 years until his 2011 retirement.

"If you do see me in a restaurant, please, just let me eat my dinner." became Andy Rooney's signature sign-off at the end of every 60 Minutes broadcast from 1978 until he retired in 2011. Although he hardly talked about his World War Two experience, even thinking "Why am I doing this? I'm scared to death. I mean, I don't have to risk my life," when the young 24-year-old Stars and Stripes corresponded climbed into a B-17 for the first time, he later justified it by saying "It just seemed like it was the honest thing to do."

Just because a reporter wasn't on the ground didn't mean he wasn't in harm's way, however—on one mission, the bomber that Rooney was flying in was hit by flak; because of this, the sergeant boasted that out of the eight journalists who were sent to cover the Eight Air Force and their daily bombing missions deep over Germany, he ended up with the best story.

Vietnam War

ABC's Anne Morrissy Merick was the first female journalist allowed to cover the war in Vietnam.

As the first true "television war", viewers were treated to a nightly spectacle of the macabre—bodies of US soldiers and Marines, North Vietnamese, civilians; the gruesome display of death; and general carnage and destruction.

While television gave war a physical sensation, reporting was still done mostly after the battle had taken place; even so, over 60 journalists lost their lives in the pursuit of covering war from a human angle.

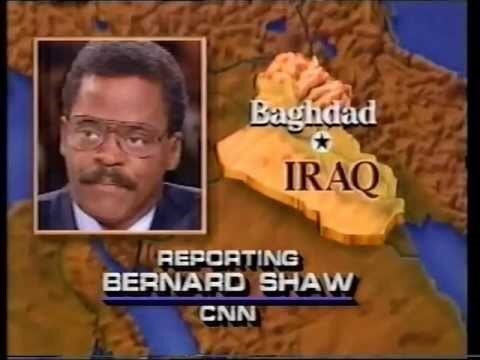

CNN's Bernard Shaw covering the 1991 Gulf War from Baghdad.

Persian Gulf War

Thanks to satellite communications, the 1991 Persian Gulf War marked the first time journalists were able to report on a battle as it was happening, giving those watching a new lens with which to view conflict. Because of CNN and the efforts of journalists like Bernard Shaw, viewers could see the battle as it unfolded, watch every twist and turn, and follow it all the way to its bloody climax.

Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

As the 21st century dawned and advancements in warfare were made, it seemed like war correspondence was on the decline; tactics such as IEDS and guerilla warfare in the mountains of Afghanistan and deserts of Iraq had made the war correspondent an almost-relic. Why, people wondered, would anyone want to risk their own life for a story when they didn't even know if they could report the story? Journalists could be ambushed at any time, so was it really worth the trouble?

Out of this dilemma, an interesting transformation took place—the soldiers themselves became journalists. When the GoPro camera was first invented in 2002, most assumed that it would only attract the enthusiast who wanted a camera to fulfill their own narcissistic desires. However, it soon became clear that the cameras weren't only useful for capturing one's "15 minutes"; warfighters were strapping them to their helmets and had them rolling while on patrol, just in case things turned south. Thanks to their efforts, the viewer got more than they ever could (or wanted)—for the first time, they actually felt like they were right there instead of watching drama through a camera a mile away.

About the Author: Ronald Hamilton, Jr. is a graduate of Arizona State University's Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communication and Media Studies. When he's not writing for COM-GAP, Ronald is a volunteer with the nonprofit Live Forever Project.