On the Shoulders of Giants

Like all subjects, the history of communication is long and winding; a tale of struggle and perseverance, triumph and loss, fortune and ruin, risk and reward. As much as it is about the inventions and communications breakthroughs, it's also a story of the people behind them.

We learn their names and commit them to memory as if they had transcended the realm of the everyday and entered the realm of the divine—Morse, Edison, Tesla, Gutenberg.

We hear the stories and repeat them as if we've heard them a thousand times—because in some cases, we have. It took Edison 999 tries on the light bulb before he got it right, we say, but he finally got it right the last time. We know the story is apocryphal, only serving as a testament to say "It doesn't matter how long it takes before you succeed, what matters is that you succeed," but it's still a fun story to tell because one, it paints Edison as a hard worker; one who wasn't afraid to try anything and everything to achieve his end goal (Edison was once asked by a reporter how it felt to fail 1,000 times; his reply was "I didn't fail 1,000 times; the light bulb was an invention with 1,000 steps.") The second reason is that we simply love round numbers.

We also love a good fight, and you don't need to look far back into the annals of history to see that they're everywhere. Edison versus Tesla (the infamous $50,000 bet that Tesla couldn't build better dynamos than the Wizard of Menlo. Edison later said it was a joke.) Hearst versus Pulitzer (the infamous newspaper war that sparked the rise of "yellow journalism" and changed newspaper reporting forever—for better and worse). Morse versus Cooke and Wheatstone (the admittedly one-sided fight by Morse to discredit the pair for sole patent of the electric telegraph, even though Morse had never met either of them.

Above all, the history of communication is the history of ideas. All of us has had an idea of one sort or another; oftentimes they're more "Wouldn't it be great if...?" and less "This could help change the world." For many inventors, their ideas never left the drawing board; for even less, they failed somewhere between first model and first production. For a very select few, their invention was so successful that they barely earned a footnote.

For these four men, they literally changed the world.

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (you'd win Scrabble forever if you ended up with that) was an enigma before he invented the printing press and printed the Bible that bore his name, subsequently cementing his place in history. The youngest son of a patrician clothier (some accounts argue that he was a goldsmith) and his second wife, Gutenberg's early years are unknown, although it's assumed that he learned the skill of metal working in some capacity. History also doesn't tell us how Gutenberg came across the printing trade, but it's widely believed that he started tinkering with the practice sometime in 1439 when he became the first European to use movable type (which is a huge technological leap in itself) and found his "Eureka!" moment a year later.

It took another eight years for Gutenberg to get serious about printing, borrowing a loan from his brother-in-law (for what, history doesn't say), but when his printing press finally started production, it was a revolution. In addition to no longer requiring writers to write everything out by hand—thus saving them from a lifetime of writer's cramp and a reduction in fine motor skills—the introduction of mechanical printing allowed for the dissemination of information and the (relatively) unrestricted circulation of it. Along with the printing press, Gutenberg also contributed

1. the use of oil-based ink for book-printing

2. adjustable molds

3. use of a wooden printing press

What made Gutenberg particularly successful was that he combined all of them into a book-production system that wasn't only practical but also economically viable for both printers and the readers who consumed their products. It also ushered in a societal revolution, as information was now free to cross borders and gave the general public at least an educational toehold on the ladder with the learned elite; the intellectual power of the politician and clergyman was finally tampered by a man with a Bible.

The great Mark Twain once wrote of Gutenberg, "What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage...for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored."

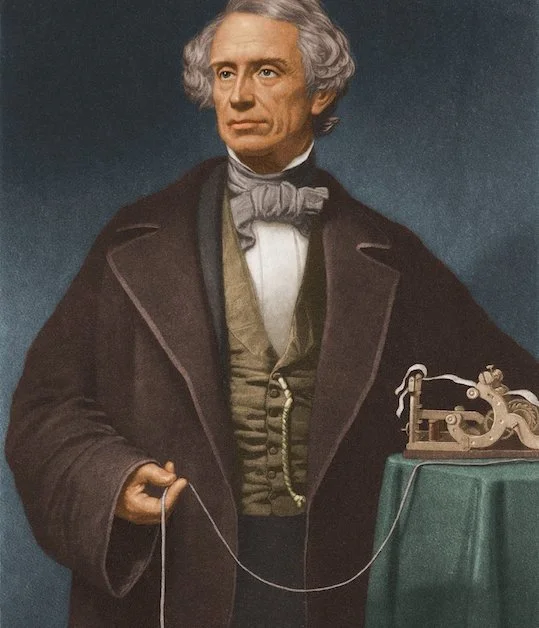

Samuel Morse

The man who would eventually lend his name to an invention and practice that are still in use today had an interesting way of arriving at it. Born the first child of a Calvinist pastor/geographer, Samuel Finley Morse studied at Yale where he learned religious philosophy, mathematics, and hippology (the study of horses), graduating with honors in 1810; during his time at the college, Morse managed to support himself financially using his skill with a paintbrush.

After several years attempting to get by with his art, Morse had a fateful encounter with physician Charles Thomas Jackson while on a returning ship from Europe in 1832; the struggling artist became so enamored with Jackson's experiments using electromagnets that he wondered if the same could be done for communication. The first patent for what would become the electric telegraph was approved on June 20, 1840.

Morse initially had issues with distance as the signal was only strong enough to be carried over a few hundred yards, but help from NYU professor Leonard Gale taught Morse the benefit of adding relays to the telegraph line at regular intervals. What originally started out as a signal of a few hundred yards turned into a signal of over ten miles.

Soon, Morse and assistant Alfred Vail were making demonstrations all over the country, with the first public demonstration of his new invention on January 11, 1838 at Speedwell Ironworks in Morristown, New Jersey; the first official demonstration came on May, 1, 1844 at the Whig party convention in Baltimore, when a message was sent from it to the U.S. Capitol announcing that the Whigs had nominated Henry Clay as their man for the presidency. Twenty-three days later, the first official message was sent from the Supreme Court chamber in the Capitol's basement to the B&O Railroad Mount Clare Station in Baltimore with the words "What hath God wrought?"

John Logie Baird

Few names are as important to the world of television as John Logie Baird, and yet hardly anyone outside of his native Scotland would know who he was. As the youngest of four children, Baird was educated at Larchfield Academy, Glasgow and West Scotland Technical College, and the University of Glasgow before the First World War permanently put his educational dream on hold (he even went so far as to volunteer with the Royal Army in 1915, but a classification of "unfit for active duty" quashed that hope also).

Undeterred in his ambition, Baird set about working on a new invention and built the world's first television set in 1923 using—among other things—an old hatbox; a pair of scissors; darning needles used to sew holes in clothes; bicycle light lenses; a used tea chest; and sealing wax and glue (these he bought himself). After a couple years of trial-and-error, the 37-year-old Scotsman managed to successfully transmit the world's first television picture (albeit in greyscale) in his lab on October 2, 1925. The first televised image in history...was the head of a ventriloquist's dummy.

Like Morse, Baird's invention soon went off like gangbusters:

- the first public demonstration of television images occurred three months later

on January 26, 2926

- the first color transmission in history occurred on July 3, 1928

- the first transmission of television pictures long-distance (over 438 miles

between London and Glasgow) occurred in 1927 from London to Central

Hotel at Glasgow Central Station

Baird also managed some success in other fields, aiding in developments to fiber-optics,

radio direction finding, infrared night viewing, and radar; however, television was without a doubt his biggest contribution. Without it, we'd never be able to get our weekly dose of reality TV.

Edward R. Murrow

"This...is London."

With those words over the radio waves, CBS journalist Edward R. Murrow would deliver his nightly reports from the bombed-out streets around London during the height of the blitz. It was 1941, and what Murrow was doing was nothing short of groundbreaking.

Murrow had the charisma and personality long before he set foot in London or even walked through the door at CBS. He was president of his high school's senior class and earned a spot on the debate team; he majored in speech at Washington State College (now Washington State University); after college, he gave a speech at the 1929 National Student Federation of America and encouraged students to be more attentive to national and world affairs. The speech got him elected president of the Federation.

After joining CBS in 1935 as its director of talks and communication, Murrow gave his first live broadcast from Vienna on March 13, 1938 on an account of the Anschluss, Hitler's annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. This broadcast itself was a marvel, as multiple reports using shortwave was unheard of at the time.

However, Murrow wasn't done making waves in the field of radio broadcasting; because his London After Dark segments were live (or as live as live could get), people didn't have to wait for the next day's newspaper to learn about what was going on an ocean away—they just had to turn on the radio. When the United States entered the war, Murrow volunteered (much to the chagrin of his bosses) to fly with the RAF and US Army Air Force so he could cover their bombing runs over Germany. He ended up flying on 25 combat missions. Librarian of Congress Andrew MacLeish praised Murrow after the war for his efforts during the blitz, saying "You laid the dead of London in our houses and we felt the flames that burned it. You laid the dead of London at our doors and we knew that the dead were our dead, were mankind's dead. You have destroyed the superstition that what is done beyond 3,000 miles of water is not really done at all."

The man from North Carolina with the commanding presence made one last contribution to journalism after his death, as the eponymous Edward R. Murrow Awards debuted in 1971 by the Radio Television Digital News Association (RTDNA) to "recognize local and national stories that uphold RTDNA's Code of Ethics".

About the Author: Ronald Hamilton, Jr. is a graduate of Arizona State University's Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Mass Communication and Media Studies. When he's not writing for COM-GAP, Ronald is a volunteer with the nonprofit Live Forever Project.